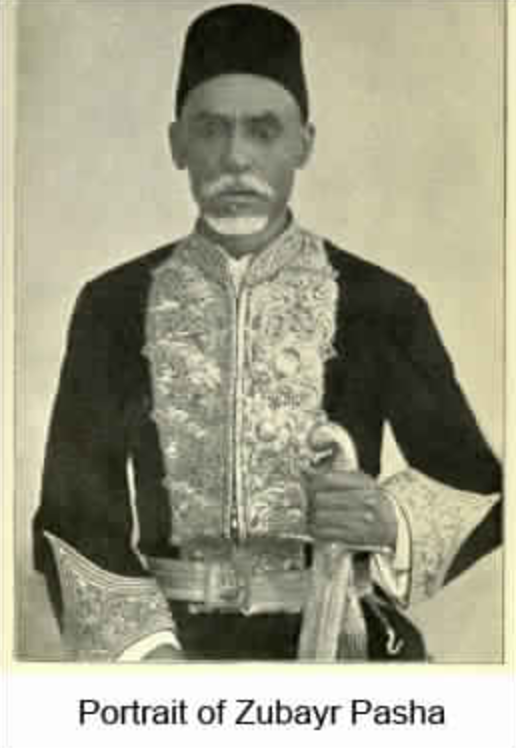

Someone colorised a black and white picture of my great-grandfather, Al-Zubayr Rahma Mansur, commonly known as Al-Zubayr Pasha. At the height of his political life, he was governor of Bahr al-Ghazal, a part of Sudan that was larger than Great Britain, Senegal, or Syria, Amir of the domains of the Ja’ilis, and given the title of “Pasha” by the then Khedive of Egypt, Ismail. It’s a much longer story, the history of Sudan-Egypt relations; but while al-Zubayr’s family had migrated to Egypt during the Fatimid times, from much further east in the Arab world, he was one of the amirs of the Ja’ili ruling families in and of Sudan, which had ruled large parts of Sudan since the 13th century, when the first Abbasi Amir, Ibrahim b. Idris al-Ja’al, founded the first Abbasi state in Sudan.

Al-Zubayr was of the Ja’ili tribe of Sudan; a Sudanese Nubian tribe, and the largest tribe in Sudan. Their name comes from the aforementioned Ibrahim Ja’al al-Abbasi, who was originally from the Hijaz in Arabia, and of the Bani Hashim, the same tribe as the Prophet and his uncle Abbas – Ibrahim Ja’al married into the local Sudanese Nubian population and so began the Ja’ili tribe, which gave Sudan many of its most noted public figures.

سلسلة نسب الزبير باشا رحمة العباسي واتصال نسبه إلى عبدالمطلب ابن هاشم ابن عبد مناف ابن قصي ابن كلاب الجامع نسبه إلى الأبوين,

هو الزبير بن رحمه بن منصور بن علي بن محمد بن سليمان بن ناعم بن سليمان بن ابي بكر بن عوض بن شاهين بن جميع بن منصور بن جموع بن غانم بن حميدان بن صبح بن مسمار بن سرار بن كرم بن ابي الديس بن قضاعة بن عبدالله حرقان بن مسروق بن احمد اليماني ابن ابراهيم الهاشم بن ادريس بن قيس بن يمن الخزرجي بن عدنان بن قصاص بن كرب بن هاطل بن ياطل بن زي الكلاع الحميدي بن سعد بن الفضل بن عبدالله بن عباس بن عبدالمطلب بن هاشم بن عبدمناف بن قصي بن كلاب بن مره بن كعب بن لؤي بن غالب بن فهر بن مالك بن النظر بن كنانة بن خزيمة بن بركة بن الياس بن مضر بن نزل بن معد بن عدنان.

A descendant of the Prophet’s uncle Al-Abbas (his full lineage reproduced above), and an illustrious leader of the Ja’ili clan, El-Zoubeir Pasha, born in 1831, ruled much of the Sudan in his era. He achieved ‘near-mythic status’ in England at the time, as the arch-nemesis of General Charles Gordon, the then British colonial governor-general of Sudan. Despite his enmity, Gordon eventually recommended El-Zoubeir Pasha be made his successor as governor-general, much to the consternation of much of Europe – but the endorsement was never implemented.

Al-Zubayr Pasha married al-Sharifa Khadija b. Omar b. Idris al-Sanusi, of the Hasani Sanusis of Morocco, one of the descendants of the Idrisis who founded the Idrisi dynasty of Morocco, and the Prophet’s gransdon, al-Hasan. Al-Sayyid Omar, Khadija’s father, and a descendant of the Prophet’s grandson Hasan, likely had an ancestor called Muhammad bin Ahmad al-Sanusi in Fez, who taught the eminent founder of the Sanusi movement and Sufi order, Muhammad bin ‘Ali al-Sanusi, whose picture is below.

El-Zoubeir Pasha and Khadijah Hanem, the last woman he married, had Muhammad Jamil (Gamil), my grandfather. El-Zoubeir Pasha had 26 sons, and 23 daughters. As a result, the offspring of El-Zoubeir Pasha today, via Khadijah Hanem and other wives in his lifetime, number a fair few, to say the least, in Sudan, Egypt, and elsewhere. His descendants included many notable figures in Egyptian and Sudanese officialdom, jurists, scholars and sages, including many from the prominent Sammaniyyah tariqah of Sudanese Sufism, which was drawn from the Qadiriyyah, the Naqshabandiyyah, the Khalwatiyyah, and others.

I shan’t comment more on that sort of family history – because, in truth, though this was the stock that my mother came from, she very seldom spoke much about it. When she did mention that background, she was modest about it, without pretentiousness, nor self-gratification.

A story in point that perhaps elaborates upon this in a way – on our last trip together, she told me, smiling and amused, of a Sudanese man she had once met in her travels. As they continued to talk, she realised he was Muslim, though his name was Michael or something similar, and was from the south of Sudan, where animism and Christianity are the religions of the majority. Curious, she enquired as to how he was Muslim, with a name that was so particularly Christian. The gentleman replied, somewhat impatiently, “I doubt that you, as an Egyptian, would know much or anything at all about this country”, as my mother had not said anything about her family background. He then continued to say: “But fine. There was this great Sudanese man, called El-Zoubeir Pasha – and at his hands, my area embraced Islam – but what would you know of him anyway. You’re just Egyptian.”

My mother smiled, nodded her head politely, not wanting to embarrass the gentleman, and went on her way. That was Laila el-Zoubeir.

My grandfather, Gamil al-Zubayr married ‘Atayat Shaheen, who was born and bred in Egypt to Egyptian parents; I remember the latter, my grandmother, far more than my grandfather, who died when I was very young. She was a kind, sweet, gentle lady, whom I called ‘Setto’, as per an Egyptian epithet for grandmothers. I remember being struck by her hands – to this day, I’m not sure why – but as my mother advanced in age, I repeatedly noticed how much her hands resembled my grandmother’s.

My mother combined a deep appreciation for her varied origins in Sudan, Egypt and Morocco, with a profound gratitude for being an Egyptian.

قصة منتخب مصر في أوليمبياد 1928: المواجهة النهائية مع إيطاليا

Her father himself, though of Sudanese and Moroccan stock, was an Egyptian patriot, and prominent national sports figure (bottom right corner of the picture above). Gamil El-Zoubeir was captain of the celebrated Zamalek football team – after, in a rather rare historical move, playing for the other eminent Egyptian football team, Ahly, for whom he played in the Egyptian Cup Finals of 1935 and 1928. But it was in 1928 that Gamil El-Zoubeir represented Egypt in the 9th Olympic Games, scoring on behalf of his country in its first international championship. Egypt came in fourth worldwide.

His daughter, my mother, Laila el-Zoubeir learnt Arabic, French and English fluently, and then took a double degree in political science and journalism at the American University in Cairo. At a time when women’s education was not as common as it is today, her father was emphatic about the need for her to have a top notch education. My mother continued to be a strong proponent of women’s empowerment, and like her father, she was for a time an Egyptian sportswoman, who almost represented Egypt at the Olympics in marksmanship.

Laila el-Zoubeir never liked to make a show of her devotion, but a weighty connection to her religion there was, leading her to make the pilgrimage to Mecca many times. In her final days, she said the following more than once:

“There is no divinity but the Divine, Muhammad is the Messenger of God – in every glimpse of the eye and every breath, as numerous as all that is contained within the knowledge of God”.

لاَ اِلَهَ اِلاّ اللهُ مُحَمَّدٌ رَسُولُ اللهِ فِي كُلِّ لَمْحَةٍ وَنَفَسٍ عَدَدَ مَا وَسِعَهُ عِلْمُ اللهِ

That was a litany of a famous saint, Ahmad bin Idris – a distant relative of her’s. That same litany was recited many times by members of her family over her and with her in her final days, and thereafter on the day of her burial in Cairo.

Generosity and Strength – the Jamal and the Jalal

In traditional metaphysics, it is said that Divine attributes are qualitatively of two types: the jalali, or the majestic, and the jamali, or the beautiful. My mother had two overriding characteristics – one was certainly jalali, and the other was definitely jamali.

Laila el-Zoubeir’s jalali attribute was, quite simply, strength – she was, without a doubt, the mightiest person I’ve ever known. Indubitably, she was elegant and graceful – but she was stout, resilient, and irrepressible. A force to be reckoned with, she was indomitable. I was with her when the doctors bluntly revealed the full extent of her condition, and how little time she had left. I had been concerned about how she might react – after all, such news understandably causes the best of us to falter, amid a flurry of confused emotions.

My mother responded, consciously and deliberately, with a determined and resolute acceptance of what was to come. When I gazed into her face, I felt I witnessed a moment of what is called in Arabic wilayah, or sainthood.

Her jalali attribute meshed into her jamali one, supporting it entirely. The jamali characteristic that she so embodied was karam – generosity, and that persisted through to the very last day she spent on this earth. It was that jamali aspect that won over people.

I perceived her power, but I witnessed her gallantry, again and again. Her chivalry meant she was polite to a fault, and big-hearted beyond reason. In her final days, she was tended to by many different medical staff, all of whom bore testimony to her bountiful largess – not one of them was permitted to leave my mother’s room before she ensured her gratitude had been expressed, the staff complimented, and given a gift of some kind. That happened irrespective of whether they had come into her room once or many times before. I was sent more than once to ensure there was a continual supply of sweets and chocolates for the nurses, and thank-you cards were written for the same. I was tasked to publicly write about the wonderful care she had received, particularly at the Jersey Hospice where she passed away, in order to encourage support for the institutions in question – she wanted everyone to know how grateful she was for the kindness they had shown, and her generosity in expressing gratitude was seemingly inexhaustible.

Towards the end of her life, my mother graciously accepted that I might assist her in managing her affairs on a much more regular basis – and I saw that charitable muscle being exercised in ways I hadn’t known of before. I’m sure there were many examples of her altruism that I will never know about. But I do know about the maid whose rent she paid for a decade, in advance. I do know about the family of a nurse who tended to my mother (a family my mother never met) and whose trips to Mecca my mother committed to financing, because of a few days of kind care by the nurse. I do know about how no-one who provided my mother a service of any kind would always benefit from her financial generosity.

That kind of selflessness was clear long before my mother was sick – and evident indeed during the toughest of times. In one instance, she was in a hospital, waiting on a wheelchair in some pain, following a test she’d had done. The test had cost a fair amount, and she asked me, ‘How do people without money do these scans?’ I replied, with a heavy sigh, ‘they don’t.’ My mother began to cry – and then resolutely declared, ‘we must help such people. We must.’ She then committed to supporting a sort of co-operative charity circle that I knew of, for precisely that kind of purpose – all the while she was in pain.

That was her focus – not herself, even when in pain, but others. I have lost track of the number of times she was in pain or in a difficult state of some kind, and yet wanted to ensure at that moment that I execute her directives to spread whatever means she might have to those who were in need, on the spot. Without waves; often without the beneficiaries even knowing about the identity of the benefactor.

Giving gifts to others was something she did right up until the end. In her final days, she was given the opportunity to have one last excursion; some people go to the beach, some visit a glorious park; and so forth. My mother chose a garden centre, which I thought meant she wanted to see flowers. I was wrong – for more than an hour, all she did was shop. She shopped for her family, she shopped for the nurses – nothing about herself. The hospice had given her the the chance to do so, though not for this purpose, but with a condition – that if she was in pain, she would say so, in order that she would return immediately. My mother said nothing about pain the entire time she was in the garden centre – but when we got back into the car to go back to the hospice, she squeezed my hand tightly. In a low voice, I asked her, Mama – are you in pain? She held her head high, pushing back the discomfort she was in, and replied ambivalently, A little bit.

She did all that shopping, silently, without the complaint, in the midst of significant pain – a pain she covered up, so as to avoid being taken back to the hospice, before she had completed her task of buying gifts for her family and those who were taking care of her.

Her munificence simply knew no bounds.

Laila el-Zoubeir’s Last Day

My mother’s last morning went very much as many mornings before it – nurses came to check on her and she described them as ‘angels’. That day, she slept a great deal, but she also had a few conversations. In the last one that I recall with me, which I think was the last she had, I believe she said two things:

“I love you too” and “Muhammad is the Messenger of God”.

Her last days were spent in Jersey of the Channel Islands, and since arriving there, she’d wanted to have anything but sunny weather – a Cairene to the core, she’d had more than enough of the sun and the heat. Yet, pretty much the entire time we’d been in Jersey, summer sunshine was the norm – until that very final day.

وَالَّذِىۡ نَزَّلَ مِنَ السَّمَآءِ مَآءًۢ بِقَدَرٍۚ فَاَنۡشَرۡنَا بِهٖ بَلۡدَةً مَّيۡتًا ۚ كَذٰلِكَ تُخۡرَجُوۡنَ

Qur’an 43:11 “He Who sent down water from the sky in a determined measure, and thereby We revived a dead land: likewise will you be raised up (from the earth)”

Thunder and lightning, accompanied by a veritable downpour – precisely the weather my mother had been waiting for. As the rain came tumbling down, litanies were uttered, invocations repeated, and worshipful recitations made.

As the day drew to an end, the storm broke, the clouds parted, and the sunset began to shine through. In the distance, I heard a song – ‘Do rei mi’, from the celebrated film, ‘The Sound of Music’, which my mother loved, and watched with her family so many years ago. it turned out that a singing group was performing in a hall nearby – and they followed it up with the Abba hit single, ‘Mamma Mia’, which I found amusing indeed.

“Mamma mia, now I really know

My my, I could never let you go”

But let her go…well.

On the 25th of the tenth Islamic month, my mother’s distant ancestor, Imam Ja’far al-Sadiq, one of the most well known descendants of the Prophet, passed away. The Islamic day begins at sunset, and about twenty minutes after sunset that day, one of the nurses speculated to me that time with my mother might be diminishing. I asked her to give me a solitary minute alone with my mother, and then to return. In the midst of that minute, I read the declaration of faith to my mother, and made a phone call to my sister who was a few minutes away. By the time the nurse came back, Laila Muhammad Gamil el-Zoubeir had breathed her last – peacefully, quietly, and with dignity.

“Martyrdom is of seven types besides being killed in the way of God: the one who dies of the plague is a martyr, the one who drowns is a martyr, the one dies of pleurisy* is a martyr, the one who dies of a pain in their stomach* is a martyr, the one who dies of fire is a martyr, the one who is crushed by a falling building is a martyr, and the woman who dies in pregnancy is a martyr.”

Within a few hours, my mother was prepared for her funeral prayer, due in no small part to my sister, of whom I was immensely proud for her commitment to her duty. I led the funeral prayer, which was performed on the island of Jersey, which my mother was so fond of.

Cairo: The City Victorious

We then embarked on preparations to return this daughter of Egypt to where her father was buried in Cairo, where she would be prayed over again in the mosque of the Lady Nafisa. All that happened smoothly within a few days, and my mother was then laid to rest near the Imam, the polymath, Muhammad al-Shafi’i – 1250 years after his passing. There were many funerals that day in that mosque, and I had resigned myself to not leading the funeral prayer. When the moment came, the imam of the mosque led the prayer indeed – but, as fate would have it, I stood in the exact same position I had stood in Jersey – right in front of the midsection of my mother’s body. We then proceeded to my family’s burial plot, where the same litanyof Ahmad bin Idris was recited. As we recited supplications over my mother’s body’s resting place, I held my sister tightly next to me. Those present saw Laila el-Zoubeir’s children stand tall, without tears, and full of pure gratitude for being her offspring.

The Friday before she was buried, I prayed the congregational prayer in Cairo – and the imam recited:

اُولٰٓـئِكَ هُمُ الۡوَارِثُوۡنَ ۙ الَّذِيۡنَ يَرِثُوۡنَ الۡفِرۡدَوۡسَؕ هُمۡ فِيۡهَا خٰلِدُوۡنَ

Qur’an 23:10-11 “Such are the inheritors that shall inherit Paradise and in it they shall abide for ever.”

And that was that. … Or kind of.

A few days after I placed my mother into the ground, I started trying to return to a normal pattern of existence and work. I found a webpage I had opened months ago during some research on my computer was still in my browser, and I hadn’t actually read it yet. On it was the last words of the famed scholar and mystic, Abu Hamid al-Ghazali, hujjat-l-Islam. So, I opened the page, and these were – and are – the last words:

“Say to my friends, when they look upon me, dead

Weeping for me and mourning me in sorrow

Do not believe that this corpse you see is myself

In the name of God, I tell you, it is not I,

I am a spirit, and this is naught but flesh

It was my abode and my garment for a time.

I am a treasure, by a talisman kept hid,

Fashioned of dust, which served me as a shrine,

I am a pearl, which has left its shell deserted,

I am a bird, and this body was my cage

Whence I have now flown forth and it is left as a token

Praise to God, who hath now set me free

And prepared for me my place in the highest of the heaven,

Until today I was dead, though alive in your midst.

Now I live in truth, with the grave – clothes discarded.

Today I hold converse with the saints above,

With no veil between, I see God face to face.

I look upon “lawh al-mahfuz” and there in I read

Whatever was and is and all that is to be.

Let my house fall in ruins, lay my cage in the ground,

Cast away the talisman, it is a token, no more

Lay aside my cloak, it was but my outer garment.

Place them all in the grave, let them be forgotten,

I have passed on my way and you are left behind

Your place of abode was no dwelling place for me.

Think not that death is death, nay, it is life,

A life that surpasses all we could dream of here,

While in this world, here we are granted sleep,

Death is but sleep, sleep that shall be prolonged

Be not frightened when death draweth nigh,

It is but the departure for this blessed home

Think of the mercy and love of your Lord,

Give thanks for His Grace and come without fear.

What I am now, even so shall you be

For I know that you are even as I am

The souls of all men come forth from God

The bodies of all are compounded alike

Good and evil, alike it was ours

I give you now a message of good cheer

May God’s peace and joy for evermore be yours.”